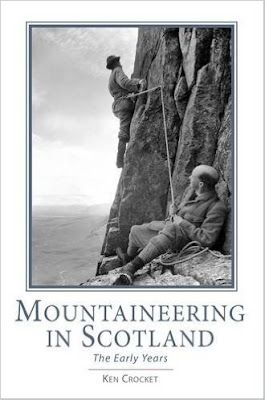

Mountaineering in Scotland (The Early Years) - Review

Mountaineering in Scotland: The Early Years by Ken Crocket (SMT, 2015)

Review by John Watson

History

is the silent traveling companion of any mountaineer. The thematic thrust of

this major work – as the back cover copy suggests – is that a knowledge of

history and landscape enhances our climbing experience. Indeed, it is necessary

to appreciate this fourth dimension as grounding for a longer-term sense of

place and deeper satisfaction of our sport. Climbing in Scotland follows a deep

palimpsest of visitation as climbers since the middle of the 19th century have

traced each other’s steps on vertical ground, deviating only where the

technology allowed deviation. Difficulty is always relative, but the landscape

is the same, the challenge always present. There is one thread between us, and

a hungering urge for return and revisit. This book looks to the first

hunger pangs.

The

initial chapters guide us through the transition from landscape and geology as

necessitous bounds of life and politics (bird fouling on St Kilda; General

Wade's military mapping) to the possibility of landscape as recreation (Forbes,

Raeburn and their ilk). This transition largely occurred in tandem with the

Victorian penchant for tourism (inspired by Walter Scott and other romantic

authors) and via academia and Natural History (geology expeditions and birding

trips, such as Raeburn's climb with bird fowler 'Long Peter' on Shetland in

1890). This broader landscape history is detailed in classic works such as Ian

Mitchell's Scotland's Mountains Before the Mountaineers (Luath, 2004),

and in the lavish production of Chris Fleet's Mapping the Nation

(Birlinn, 2011), but Crocket here gives us some rediscovered historical gems

from the climbing literature, such as Raeburn's account of Long Peter's rock-climbing

skills (and bold attitude) on the Lyra Skerry. It reads as though Long Peter is

exhibiting to Raeburn an enjoyable athletic skill he has cultivated, focusing

down on the exposed moves on the 'bad bits', with the aim of collecting eggs

somewhat incidental to the immediate difficulties. Eggs are apt metaphors for

what is about to develop.

The

period 1866 to 1886 sees a nascent exploration of the steep cliffs in the

highest ranges, largely in Skye, frequented by the likes of William Naismith and

of course the dynamic duo of Norman Collie and John Morton Mackenzie in a

golden era of exploration on the gabbro walls of the Cuillins. There are some

interesting technical asides on alpenstocks and a fascinating portrayal of that

old stalwart – the 100 foot hemp rope – as an illusory piece of protection. It

is remarkable to think that these climbers, in clumping hobnails, found the

delicacy of approach and toe-touch to negotiate difficult ground for around 80

years as effectively solo ascents, with nothing but a psychological umbilical

threaded between them. Sometimes it was window-sash cord.

The

mini-biography of Collie contained within these chapters is told with fondness

and the astonishment of a modern climber at the underestimation of the

achievements of these early explorers. Collie finished off the intricate

mapping of the Cuillin Ridge peaks and bealachs when the OS had only managed 8

measurements. His life-long relationship with JM MacKenzie is one of a

friendship bound in landscape through time, and immortalised in it with their

names suitably Gaelicised on neighbouring peaks of the Cuillin, echoing the

twin headstones side by side in Struan graveyard. The writing does well here to

take the reader beyond the catalogue of ascents and climbs towards the

character and style of the two great climbers, and captures the refreshing

thrust of youth finding in the world novelty and thrill rather than relativity

and memory (we tend to imagine Collie and MacKenzie as grizzled old guides

moping around the Slig Hotel).

It

is to be commended that the volume looks at the wider context of landscape and

politics, as quite naturally the arena for climbing is set in what were

effectively 'private' estates in the Highlands, with land access and rights for

walking becoming a particular and newsworthy feature from the Victorian era

onwards. This mostly urban leisure coterie suddenly found itself encountering

the entrenched enclosure mentality of landowners that crofters and Highlanders

had been suffering for centuries. These access wars included the Glen Tilt

botany expedition of 1847 and led to legal action and to the Scottish Rights of

Way Society – notably a group able both to afford legal representation and

co-ordinate their resistance without fear of eviction or worse. James Bryce, a

Glasgow-born Liberal MP, was foremost in representing this movement as far as

Parliament in the Access to Mountains (Scotland) Bill of 1894. It would be

2003 before this statutory revolution would win through against feudal landownership

as the Land Reform (Scotland) Act and modern climbers should do well to realise

their now-enshrined rights were born of other centuries.

This

era of curiosity in all things high and steep (largely 1866 to 1914 in this

book) mirrored a wider social mobility and of course greater economic

capability and leisure. This led to much professional occupancy in the

Highlands with meteorologists, botanists, surveyors and the like, and was

accompanied by the rapid growth of mountaineering societies trying to emulate

the Alpine Club enthusiasm for high peaks. The

Cairngorm Club was founded in 1889, followed shortly by the Scottish Mountaineering Club, the birth

of which was induced by the Glasgow-based William Naismith, who published

appeals for such a society in the Glasgow Herald. Its initial roll-call

consisted of academic professors, baronets, doctors, lawyers, reverends,

businessmen etc. and it would be notable that a separate Glasgow-based club (The Creagh Dhu) would later arise from

the working class as a reaction perhaps to the discomfiture of climbing next to

a wealthier class of mountaineer. But these were not men and women bred to

exclusion and Mason-like enclosure. Crocket points out here the greater social

benefit of these clubs (aside from keeping the wealthy amused), such as the

ancillary activities of recording their tradition in journals and area guides

(the SMC Journal first appeared in January 1890), organically spreading

experience, technology development and skills-based knowledge to a wider

audience of potential mountaineers. These days we often underestimate the

difficulty of actually sourcing and spreading knowledge in pre-internet days,

when people valued face-to-face meets as essential knowledge-dumps or social Googling.

Local newspapers, limited guidebooks and young club journals were the only

repositories available for climbers to spread their enthusiasm to the wider

population, and the author interestingly points out the absence of listing

mountaineering as a 'sport' in Thorstein Veblen's sociology text The Theory of the Leisure Class,

published in 1899. Mountaineering, it seemed, would always fall outside the

pale of public consciousness and was still very much the privately documented

leisure of the wealthy (at least until access, technology and skills became

cheaper and more public after the wars of the early 20th century). It is an odd

irony that the first SMC journals, entertaining snow-globes of those early

mountaineering moments, can now be read online by thousands more people than

were ever first read on publication. The recording and diarising impulses of

these early pioneers is now digitally embedded (thanks to such print and

electronic publishing efforts by the SMT) and consequently gives us a longer perspective

than the fading legacies of oral history, or indeed total silence on the

matter.

With

the publication of ‘Hugh Munro's Tables of Scottish Mountains’ in 1891, along

with completion of the Fortwilliam rail-route in 1894, technological and industrial

expansion would transform the mountaineering pursuits. Rock-climbing, rather

than a nascent Munro-bagging, as the author notes, was the natural challenge

for the club climbers, many who were prepared to walk huge distances to ascend

climbs, compared these days to often only a maximum ‘two hours from the

car-park’. The author reproduces some of the key documentaries of ascents in

this era from the journals: epic rounds of Munros; appalling gully assaults

such as the infamous Black Shoot; as

well as the early fascination with Cir Mhor’s NE Face in the 1890s, where today

we mirror this adventure with the technical stealth-smearing on the blank slabs

on the southern flanks of the Rosetta Pinnacle (then beyond the capability of

boot technology). In fact, the whole book feels like this: a kind of mirror

image of technical and wondrous ascents on unknown rock territory (in tweeds

and hobnails rather than Pertex and rubber), with the appalling watershed of

WW1 separating the generations of rock climbing in Scotland. It is no underestimation

to say the rock-climbing community had to evolve again from scratch, with new

fascinations and technologies, and with new appetites for risk and adventure

untainted by the realities of war.

Ben

Nevis receives its fair attention with accounts of ascents by William Inglis

Clark, Harold Raeburn, even George Mallory amongst others, in the era when Ben

Nevis was actually less forbidding with the shelter of the Observatory and

Summit Hotel should the weather cave in (ascents often started with a ‘down and

up’ climb to the hotel, rather than the modern-day ‘up and down’ to the CIC

Hut). The bulk of the book recites the gradual opening of such great cliffs of

Scotland, the exploration of gullies and ridges, and the gradual mental mapping

of vertical areas, the names of which are often used as reference or access

these days (Tower Ridge, Gardyloo Gully, Observatory Buttress etc.), the drive to deviate and explore being

what it is. Perhaps the most impressive rock ascent of the era was Raeburn’s

solo summer ascent of Observatory Ridge

in June 1901. This long ‘V Diff’ route still feels exposed and tricky in our

modern era and shows the qualities of route-finding and composure this

generation possessed. Raeburn would continue to dominate the major ascents on

‘The Ben’ with the impressive winter ascent of Green Gully in 1906, and Raeburn’s

Buttress in 1908. In Skye, the first complete ascent of the Cuillin Ridge

was made by Shadbolt and MacLaren in June 2011, and this seems to round off the

achievements of this remarkable generation of climbers, despite their lack of

awareness of what lay round the corner. The last chapter ‘The Darkness Drops’

is an aptly named epitaph for those who didn’t come back from the First World

War, and marks a significant reset in the nation’s consciousness as to the

purpose of going into the hills. It would be a long time before those that were

left had the energy, or even the urge, to return to the hills.

We

should congratulate Ken Crocket on a tour-de-force of reanimation and for his

dedicated enthusiasm for a lost generation of climbers, rapidly in danger of

being forgotten not only by modern climbing, but by the obliviating erosion

of fashions, and dare I say it, the blizzard of the digital present.

Reading this terrifically detailed chronology of an era when the cliffs were

largely all virgin territory, it is chastening to think that not a single

climbing fatality was registered, and that the self-reliance of this generation

far outweighs the blithe reliance on technology we could perhaps be accused of

these days! That is not to diminish

modern achievements, but one of the crowning achievements of this book is that

it puts in true perspective the depth of resilience and judgment these early

climbers brought to the Scottish hills. The photographic plates are a highlight

and I hope the SMT continues to deposit more historical photographs and

documents on their website http://www.smc.org.uk/

along with their continued devotion to recording a sport and tradition which is

embedded in landscape and history, and all the better for it.

This

wondrous book should inspire any climber in Scotland to return to old haunts,

wearing a new layer of understanding and respect, a little tweedier perhaps,

and maybe, briefly, without a phone signal.

Available

to buy on Amazon