Bouldering Essentials review

I am glad every time I see a new independent publisher - Three Rock Books (AKA Dave Flanagan from Dublin) - as it's a tough, odourless, online world for those who still like the smell of freshly printed gloss paper. Especially publishers who design and produce such quality books on bouldering as this, bringing another life-giving breath of literature to the genre.

Bouldering may use the same techniques as its alma mater of traditional climbing and mountaineering, but perhaps it is becoming more akin to athletics, parkour, and the like - exhibiting a freestyle skateboarding ethos rather than the bastardized spasms of an alpinist's practice routine. Hence it needs a book of its own, one that shows with refreshing self-reference, and I mean that in a positive way, the shape of itself: its techniques and ambitions; its landscapes and its own arena. So Three Rock Books has produced a lavish introduction to the game: Bouldering Essentials.

I can't recommend this book enough for the boulderer starting out on the whole adventure - I wish I'd had it twenty years ago. I'd have been a better climber, I'd have touched much more rock and I'd probably have burnt my ropes. Bouldering Essentials is a book for boulderers, or people who want to become better boulderers, whether this process eventually has a rope at the end of it or not. Face it, the bouldering walls are full of people with no real urge to necessarily try roped climbing, let alone the winter game, for all their health benefits and risk-management positives. That's the overwhelming feeling I got from reading through this book - Dave Flanagan is talking as if bouldering had never heard of traditional climbing, or as if mountaineering was really born of bouldering (which I think is probably true). And that's good for bouldering to acknowledge. Let's assume it is something like an urban skateboarder talking about movement, balance, tricks and routines; who has never seen Big Wednesday, let alone a coastline under a swell. I know the author - Dave Flanagan - loves his trad, but this book does something unique and has given bouldering a voice without an echo.

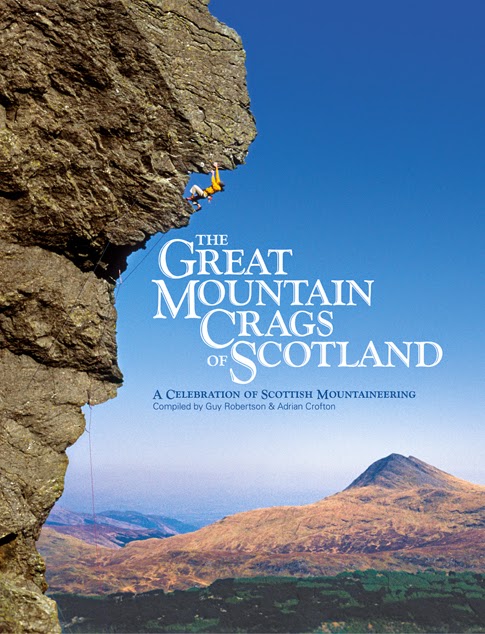

So, the book? The cover - boulderer in Rocklands isolated against a blue sky under a soaring prow of orange rock - sets the scene and the quality of the interior. A playful foreword from one Johnny Dawes shows us that even in the grip of high alpinism, the boulders still attract the framed element of play that is the core of climbing. The introduction sets us on the right track straight away: 'Climbing is a primal human instinct . . . bouldering is playful and accessible'. A section on beginning naturally leads us into the initial state of mind of the beginner, which is as good a practice for experts as it is for the learner, before the book moves on to equipment and techniques. The clean text and concise paragraphs are well written and don't overburden the beginner, and are refreshing for the veteran. It's good to relearn that 'it's impossible to push your limits without falling' (some experts are too afraid 'not to flash' a problem) and the sections on movement and dynamics, in tandem with superbly edited photography, explain the bewildering lexicon of bouldering to the beginner in clarified explanations: 'ah ha, so that's what a gaston is!' Indoor gyms and walls and training regimes give body to the middle section of the book where the beginner is setting goals, before the final section (understandably but for me wistfully truncated) shows us some of the lavish landscapes where the boulderer can ply these skills. There is plenty enough online, you can google these places and plan your next holiday destination to frustrate the patience of your partner/kids/parents etc.

So, the book? The cover - boulderer in Rocklands isolated against a blue sky under a soaring prow of orange rock - sets the scene and the quality of the interior. A playful foreword from one Johnny Dawes shows us that even in the grip of high alpinism, the boulders still attract the framed element of play that is the core of climbing. The introduction sets us on the right track straight away: 'Climbing is a primal human instinct . . . bouldering is playful and accessible'. A section on beginning naturally leads us into the initial state of mind of the beginner, which is as good a practice for experts as it is for the learner, before the book moves on to equipment and techniques. The clean text and concise paragraphs are well written and don't overburden the beginner, and are refreshing for the veteran. It's good to relearn that 'it's impossible to push your limits without falling' (some experts are too afraid 'not to flash' a problem) and the sections on movement and dynamics, in tandem with superbly edited photography, explain the bewildering lexicon of bouldering to the beginner in clarified explanations: 'ah ha, so that's what a gaston is!' Indoor gyms and walls and training regimes give body to the middle section of the book where the beginner is setting goals, before the final section (understandably but for me wistfully truncated) shows us some of the lavish landscapes where the boulderer can ply these skills. There is plenty enough online, you can google these places and plan your next holiday destination to frustrate the patience of your partner/kids/parents etc.

Looking through this world venues section (chapter 10), and the stunning landscapes where boulderers play, shows how bouldering really has moved beyond the 'little brother' image of mountaineering, to become a kind of meta-climbing. It shows small ascents in big places as somehow epic; construed and applied to the rock in a much more intimate manner. This is a book telling people, for the first time, that this is fine on its own - you don't have to worry about all that 'next step is Everest' crap. Bouldering is becoming in and of itself, it is all consuming if you let it. Hell, I've forgotten I ever had a harness, and this book tells me all I need to feed the rat!

Get yourself a copy and get bouldering >>>

Bouldering may use the same techniques as its alma mater of traditional climbing and mountaineering, but perhaps it is becoming more akin to athletics, parkour, and the like - exhibiting a freestyle skateboarding ethos rather than the bastardized spasms of an alpinist's practice routine. Hence it needs a book of its own, one that shows with refreshing self-reference, and I mean that in a positive way, the shape of itself: its techniques and ambitions; its landscapes and its own arena. So Three Rock Books has produced a lavish introduction to the game: Bouldering Essentials.

I can't recommend this book enough for the boulderer starting out on the whole adventure - I wish I'd had it twenty years ago. I'd have been a better climber, I'd have touched much more rock and I'd probably have burnt my ropes. Bouldering Essentials is a book for boulderers, or people who want to become better boulderers, whether this process eventually has a rope at the end of it or not. Face it, the bouldering walls are full of people with no real urge to necessarily try roped climbing, let alone the winter game, for all their health benefits and risk-management positives. That's the overwhelming feeling I got from reading through this book - Dave Flanagan is talking as if bouldering had never heard of traditional climbing, or as if mountaineering was really born of bouldering (which I think is probably true). And that's good for bouldering to acknowledge. Let's assume it is something like an urban skateboarder talking about movement, balance, tricks and routines; who has never seen Big Wednesday, let alone a coastline under a swell. I know the author - Dave Flanagan - loves his trad, but this book does something unique and has given bouldering a voice without an echo.

So, the book? The cover - boulderer in Rocklands isolated against a blue sky under a soaring prow of orange rock - sets the scene and the quality of the interior. A playful foreword from one Johnny Dawes shows us that even in the grip of high alpinism, the boulders still attract the framed element of play that is the core of climbing. The introduction sets us on the right track straight away: 'Climbing is a primal human instinct . . . bouldering is playful and accessible'. A section on beginning naturally leads us into the initial state of mind of the beginner, which is as good a practice for experts as it is for the learner, before the book moves on to equipment and techniques. The clean text and concise paragraphs are well written and don't overburden the beginner, and are refreshing for the veteran. It's good to relearn that 'it's impossible to push your limits without falling' (some experts are too afraid 'not to flash' a problem) and the sections on movement and dynamics, in tandem with superbly edited photography, explain the bewildering lexicon of bouldering to the beginner in clarified explanations: 'ah ha, so that's what a gaston is!' Indoor gyms and walls and training regimes give body to the middle section of the book where the beginner is setting goals, before the final section (understandably but for me wistfully truncated) shows us some of the lavish landscapes where the boulderer can ply these skills. There is plenty enough online, you can google these places and plan your next holiday destination to frustrate the patience of your partner/kids/parents etc.

So, the book? The cover - boulderer in Rocklands isolated against a blue sky under a soaring prow of orange rock - sets the scene and the quality of the interior. A playful foreword from one Johnny Dawes shows us that even in the grip of high alpinism, the boulders still attract the framed element of play that is the core of climbing. The introduction sets us on the right track straight away: 'Climbing is a primal human instinct . . . bouldering is playful and accessible'. A section on beginning naturally leads us into the initial state of mind of the beginner, which is as good a practice for experts as it is for the learner, before the book moves on to equipment and techniques. The clean text and concise paragraphs are well written and don't overburden the beginner, and are refreshing for the veteran. It's good to relearn that 'it's impossible to push your limits without falling' (some experts are too afraid 'not to flash' a problem) and the sections on movement and dynamics, in tandem with superbly edited photography, explain the bewildering lexicon of bouldering to the beginner in clarified explanations: 'ah ha, so that's what a gaston is!' Indoor gyms and walls and training regimes give body to the middle section of the book where the beginner is setting goals, before the final section (understandably but for me wistfully truncated) shows us some of the lavish landscapes where the boulderer can ply these skills. There is plenty enough online, you can google these places and plan your next holiday destination to frustrate the patience of your partner/kids/parents etc.Looking through this world venues section (chapter 10), and the stunning landscapes where boulderers play, shows how bouldering really has moved beyond the 'little brother' image of mountaineering, to become a kind of meta-climbing. It shows small ascents in big places as somehow epic; construed and applied to the rock in a much more intimate manner. This is a book telling people, for the first time, that this is fine on its own - you don't have to worry about all that 'next step is Everest' crap. Bouldering is becoming in and of itself, it is all consuming if you let it. Hell, I've forgotten I ever had a harness, and this book tells me all I need to feed the rat!

Get yourself a copy and get bouldering >>>