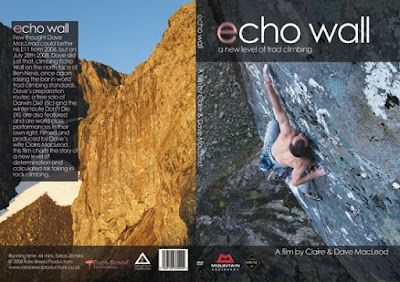

This is an exceptional film about the bizarre relationship between mountains, humans and risk. No matter that it features probably the most serious high-end route on the planet, Dave and Claire MacLeod have created a unique vision of obsession, determination and stress. 'Echo Wall' captures all the emotional trauma of climbing at the limit in a situation where failure is unacceptable. As an independent team, Claire and Dave have obviously worked really hard to bring this film together and they succeed in showing some of the sacrifice and pain of climbing what is effectively E12 on the most inhospitable mountain in Britain.

'The Ben' is not always inhospitable and the film opens with some fine time-lapse images of clouds clearing and alpen-glow washing down the peppered eminence of The Comb high in Coire na Ciste. Some helicopter shots give us the right impression that the north face of this mountain is something truly alpine and alien to the lush land 4000 feet below.

Dave is introduced training for the route in Glen Nevis, with some toe-quivering, arm-popping bouldering on the hardest lines in the glen. This helps explain the level of physical fitness Dave needs to achieve to stand a chance on Echo Wall, as well as the sheer element of luck in catching a weather window... maintaining fitness and confidence while the Ben is shrouded in cloud and rain becomes the dominant theme as the summer wears on.

A welcome interlude is the interview with Jimmy Marshall, who was pushing his own climbing boundaries on the Ben in its heyday. He warns us of the treacherous nature of the mountain as he relates a story of rescuing friends from sudden storms and of what he learnt from the mountain: the importance of climbing in the purest style and accepting that the mountain has more to teach in humility than in bravado.

Suitably chastened, Dave sets out to Spain to work on his mental resolve by soloing an 8c called Darwin Dixit. This piece of footage is astonishing. A birdsong early morning at Margalef, Dave is seen struggling in silent internalisation before he jumps onto the route without ropes and pulls through its horrific mono-crux with cool style and strength to spare.

May comes and snow still lies melting over the route. A humorous interlude ensues as he digs away the snow in manic bare-topped craziness, with Claire questioning his sanity. An E8 is despatched as preparation, then 'working' the route on a shunt as the mists boil round and the weather threatens to scupper the whole project. Dave returns to the lower glen to climb the Sky Pilot 9a traverse in atrocious weather, attempting to hang on to his hard won fitness and mental fortitude. All this poor weather and constant mental struggle leads to an acceleration of doubt and despair before a weather window in late July...

then he steps on to the route for real...

This is where all that preparation matters, but it is still a terrifying prospect as Dave leans backwards into the hands-off rest before the lonely and desperate climbing of the headwall above. The accompanying voice-over thoughts of Claire and Dave as he is about to set out on the crux is the most poignant moment in the film and for me the whole crux of the game as Dave sets out alone on a very exposed sequence of climbing. The irreversible nature of risk-taking in climbing is here perfectly captured in a few highly charged sequences - thereafter it is all relief as Dave unties at the top of the route and solos off the easier section.

This is a film that educates us in how to approach traditional climbing. The thoughtfully narrated surgery on his inner self shows Dave as a fiercely analytical climber in tune with his physical abilities, but human enough to show the endless struggle with doubt and nadirs of confidence that beset us all when climbing. The music, largely by the late and lamented Martyn Bennett, gives the whole film a high-voltage, swash-buckling energy and I must admit to some 'Braveheart emotions' as Dave runs the Tower Ridge as a warm-up before working the route!

I'd recommend everyone buys a copy. This is a remarkable achievement by Claire and Dave and a great piece of film-making in the most difficult of emotional and physical conditions.

Pre-orders are available from Dave's blog site.