I must admit that, as a publisher, when the complimentary copy of Scottish Rock Vol. 1 dropped through my letterbox I had to reappraise my ideas as to what a guidebook should be... the quality of the production is immediately stunning, the layout is colourful and clear with apt and well-chosen photography, along with excellent photo-topos of the crags and simple clear maps. What's more, the 480 pages make this an incredible value-for-money book (£23.00) and shame a lot of other publishers as to what can be packed into a pound of publishing (myself included!).

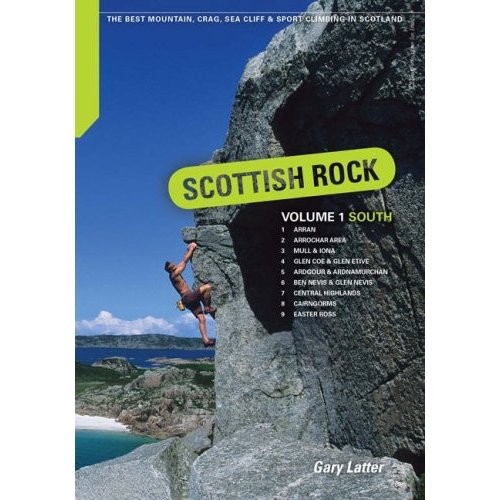

The glossy cover shot of a bronzed, sunglassed Julian Lines soloing on Erraid's pink granite above peppermint seas might make you think this a Peleponnesian guide, but in reality we do get days like this in Scotland and it is a mouth-watering advert for the remote pleasure of climbing in Highland Scotland and what lies within the guide.

And this is what this first volume of two is designed to represent - the best of the climbing in Highland Scotland, from the Highland Boundary fault all the way to the Islands. From a first read-through, the represented routes cross all the grades and seem fairly chosen. Gary Latter (the author) is an experienced climber in Scotland and knows his stuff, also being responsible for a lot of the routes, so if you see his name often, that's not hubris, it's just he put up most of the remote extreme routes in Scotland in the last thirty years! Arran, for example, gets a complete spread of grades from Souwester Slabs (V Diff) through to the modern The Sleeping Crack (E6), with excellent photo-topos showing the lines of the face as you would see it on approach.

I guess my only trouble was with the strict geological demarcation of the book's area. I know the Highland Boundary fault is the starting point for the Highlands, but it seems unfair to have left out the great beacon of Scottish climbing which lights up what is ahead of you... Dumbarton Rock. It may be a scruffy place and I understand why aesthetically it might be left out, but it is so close to the area concerned, and is passed on all journeys up the west coast - its tremendous natural lines illustrate the Scottish Ethic perfectly and what one can expect from climbing in a style sense in Scotland (exposure, exhilaration, fight). Anyway, it's a small gripe, but maybe a couple of pages could have covered Dumbarton and it does have a toehold on the Great Fault! But editing such a book demands sacrifices, so I shouldn't go on about this.

The most attractive sections of the book were the new crags and the remote delights of Mull, which will become a little busier I guess. The hidden gems of deep-water solos, bouldering and hard single-pitches on glorious granite can be found in the pages on Erraid, Scoor, Garbh Eilean and Iona... this is given an overdue focus as these areas are some of the finest places to be, let alone climb! The photographs will do the rest.

Glen Nevis gets a deserved wad of pages, as does the Ben itself, with a tardis-like compression of the amount of quality climbing up there. Ardnamurchan and Ardgour have some awe-inspiring lines and get a good section devoted to them. Other classic areas are given due quality representation: the Coe , the Cairngorms and Arrochar (some great pics in all).

I can only congratulate Gary on a well-written and informative (if not exhaustive) representation of Southern Highland climbing. The research and time he has poured into this is simply mighty, and I know how big a country this is to cover! The history sections and the introduction are all absorbing and the weather chapter was amusing ('in the Outer Hebrides, gales are recored on over 40 days of the year'), the Geology chapter summarised our deep time very clearly and there was some sport climbing and bouldering represented within the guide as well which I was glad to see.

Lastly, I'd just have to say well done to Pesda Press for the immaculate production of this guide, the clean and attractive design and the value for money. It is not cheap producing such quality and I salute their bravery.

This is a must-have guide for the dedicated Scottish climber or simply the visiting climber.

It's the first Scottish guidebook I'll reach for when Heather points to medallions on the evening forecast...