The Trossachs - In Praise of the Victorian

'The use of Loch Katrine to supply Glasgow has its origins in Victorian times. In the early part of the 19th Century, a mere 30 public wells - and a handful of private ones - provided the city’s only sources of water. In 1848, after a second outbreak of cholera again decimated the poorest inhabitants, moves began to bring the water supply under municipal control in an attempt to overcome the growing public health problem.

Five years later, John Fredrick Bateman - a civil engineer of considerable contemporary repute - concluded his study to find the best potential source for Glasgow, recommending the high quality water of Loch Katrine. The House of Commons passed the necessary bill in April 1855. The resulting supply system took three and half years to complete and involved the construction of a dam on the loch, 26 miles of aqueduct, a similar length of trunk mains, 46 miles of distribution pipes and the Mugdock storage reservoir at Milngavie. Queen Victoria herself officially opened the scheme - seen as the engineering marvel of its day - on 14 October 1859.'

Five years later, John Fredrick Bateman - a civil engineer of considerable contemporary repute - concluded his study to find the best potential source for Glasgow, recommending the high quality water of Loch Katrine. The House of Commons passed the necessary bill in April 1855. The resulting supply system took three and half years to complete and involved the construction of a dam on the loch, 26 miles of aqueduct, a similar length of trunk mains, 46 miles of distribution pipes and the Mugdock storage reservoir at Milngavie. Queen Victoria herself officially opened the scheme - seen as the engineering marvel of its day - on 14 October 1859.'

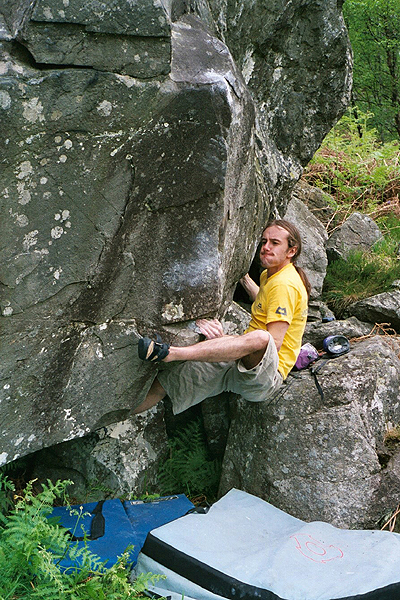

Lock Stock & Barrel - Font 7c - Trossachs - Dave MacLeod

Lock Stock & Barrel - Font 7c - Trossachs - Dave MacLeodSome boulder problems, like Victorian engineering, require bloody hard work, pain, long mileage and success against the odds. Ingenuity and opportunity are the key words...this is how I feel about 7 metres of rock that has taken me over 800 miles of driving just to complete. Lord knows why we do it, but I had 'seen' this line as a remote possibility while attempting to repeat Dave MacLeod's 'Lock, Stock and Barrel', a desperate one-move Font 7c. Dave popeyed his cheeks, gave it some spinach and it was despatched...I did the Popeye impression but not much else... however, the right hand prow of this boulder, if I could shift a little boulder scree, I thought might provide an escape from the cave other than the MacLeod power-out.

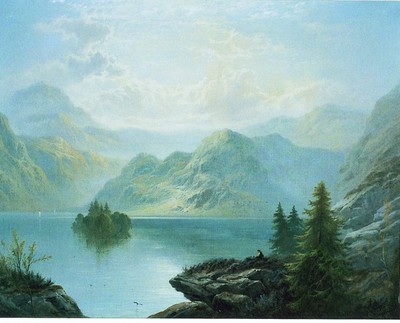

Loch Katrine was a devious piece of Victorian engineering... invisible sandstone conduits lead from Lochs Arklet to Katrine and then down underground in infinitesimal gradients all the way to Glasgow via Mugdock, where it finally ends up in your kettle or your bath. The stuff that comes out my tap still has the clarity of Trossachs water - a lucid thing brought to us by clever Victorians and the ghosts of hired-hand navigators. It was also the start of the whole tourism thing in the Trossachs... blame Walter Scott for the tinny incomprensible wah-wah sounds from the Waverley as it steams past the Trossachs boulders. It is a painfully beautiful spot in the quiet light of a misty morning.

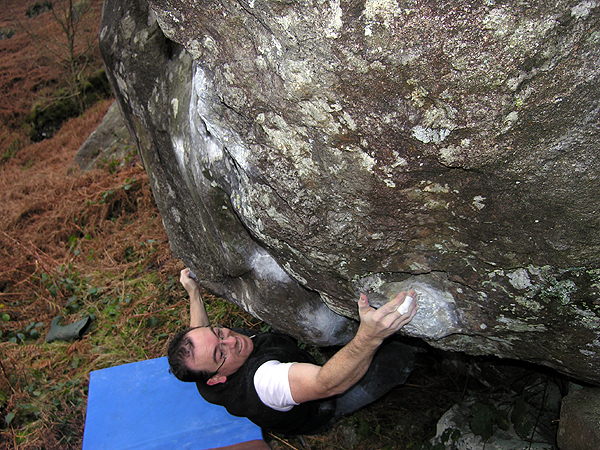

On this final bright morning, with the mist lifting, I was not expecting success. I had arrived again with my sack of bouldering industria (chalk, wire brushes, mats, poles, cameras, surgical tape), intent on working the problem again. The only thing I didn't need to bring was water, which generously bubbles past the Sebastopol boulder (named after a Navigator camp, itself named after the Crimean war city). Here I lay under the cave contemplating the odds of success on the poor holds I had been given to reach the hanging prow. This must have been at least my tenth session on this problem. It went okay from a start from an embedded boulder, but the real problem was coming out of the cave and getting to this precarious powerplay over the embedded boulder (without wilting and lying back on it in failure). Tension through a heel-hook had to be maintained to get into a position where the painful quartz nubbins on the prow might be gained. I got this several times, strong on it now, but for the life of me couldn't get my heel-lock unlocked to replace as a toe-push and move on... finally an ingenious sequence of unlikely toe-holds allowed me to power out up to the arete, where I wobbled round on to the slab and finished exhausted on the little summit. There was only one name in my head for all the suffering this problem took me... 'The Victorian'.

I sat there, invigorated and lucid, the sky had clouded over, Loch Katrine had stilled itself, nothing moved but the little burn bubbling away. Everywhere the trees and hills replicated themselves in the loch. Only in bouldering does time vanish so easily... I would not have been surprised to have seen a posse of Victorian engineers with their theodolites and stove-pipe hats.

John Watson 'working' The Victorian, Font 7b+,Trossachs boulders